Back

to the Books and Other Writing page

Back to the Archive Contents page

by Elijah Wald

Originally published in Tower Pulse, 2000

Dolly Parton is sitting in her suite in the Hotel Pierre, high above Central Park. She is wearing tight black Capri pants and a spectacularly form-fitting blouse, her hair is fashionably feathered, and her eyes impossibly large and perfectly made-up. She looks like a movie star, not like a bluegrass singer and one of the most successful and prolific songwriters in country music. Dolly Parton is sitting in her suite in the Hotel Pierre, high above Central Park. She is wearing tight black Capri pants and a spectacularly form-fitting blouse, her hair is fashionably feathered, and her eyes impossibly large and perfectly made-up. She looks like a movie star, not like a bluegrass singer and one of the most successful and prolific songwriters in country music.

Which may be the reason that Parton continues to surprise a lot of people. They are so used to seeing her on television, looking, in her own evocative phrase, “like a drag queen’s Christmas tree,” that it is startling to find her recording acoustic, folk-based music on a specialty bluegrass label, or to realize how many of the best songs continue to come from Parton’s own pen.

“Well, I’m just a whole lot to deal with,” Parton laughs. “People look at me and they think hair and boobs and personality and gaudy clothes and I have to overcome myself. But the people that have followed my career for a long time, they know what all I do, and most of them take me serious as a writer, which is always a great compliment to me.”

Parton has written most of her own hits, back to the late 1960s, as well as number one songs for artists like Merle Haggard. Her “I Will Always Love You” topped the country charts twice for her, in 1974 and 1982, before Whitney Houston’s 1992 pop cover became one of the biggest-selling records in history.

“I’ve been making up songs since I was like a little bitty kid,” Parton says. “Before I even remember, my mother used to find it fascinating that I could rhyme things, and she used to write them down on paper. I was always touched with stories and I could always rhyme anything. Something will come to me as a thought or feeling, and automatically I come up with a rhyme line; that’s just how I express myself.

“It’s my favorite thing that I do, and even with all my other work, at least twice a year I’ll try to set aside two to three weeks to go away and write. Sometimes I can’t get in the flow, but I usually can after a few days if I’ll just stick with it. And once that flow starts to go, then they just come rolling out. But not a day goes by that I don’t write down a title or some lines or some thoughts. So in the course of a year I’ll probably write anywhere from fifty to seventy-five songs.”

Despite her continued productivity, Parton has found herself largely frozen off the charts in recent years, along with contemporaries like Haggard, George Jones and Willie Nelson. In the old days, a country star could grow old in the music, but the last dozen years have seen country become as youth-centered as any other aspect of pop. For a while, she tried to hammer her way past the generational barrier, recording duets with Vince Gill and Ricky Van Shelton, but by the late 1990s she was feeling frustrated: “I was between labels, and they weren’t really playing me on the radio, and I thought, ‘Well, why am I busting my ass for something they don’t even want? I need to figure out what it is I want to do, and what I can do best.’”

First, Parton cut a full album of recent compositions, “Hungry Again” (Decca), working with a cousin’s band in his home studio. A strong collection that ranged from quiet acoustic songs to raging honky-tonk, it attracted little attention from either critics or fans. Then Parton happened to be having dinner with producer Steve Buckingham, the head of Vanguard Records. Vanguard is part of the Welk Music Group, which had recently acquired the bluegrass label Sugar Hill. Buckingham happened to mention that he had recently seen a poll of bluegrass musicians which placed her at the top of a list of performers they would like to see make a bluegrass album.

“He just told me that for fun, but I said, ‘Really? I ain’t doing anything in the next two months, music-wise. You want to produce a bluegrass album with me?’ And he said, ‘Are you kidding?’ And I said, ‘No, I’m not kidding.’ So, two months later we had it out.”

That was 1999’s “The Grass is Blue,” which may be the most critically-acclaimed album of Parton’s career. It featured an A-team of players, including Jerry Douglas on dobro, Sam Bush on mandolin, Bryan Sutton on guitar, and Stuart Duncan on fiddle, with Alison Kraus, Patty Loveless and Rhonda Vincent adding back-up vocals. The songs were a mix of bluegrass standards, Parton originals, and quirky choices like Billy Joel’s “Travelin’ Prayer.”

They cut most of the album live in the studio, a rarity on the modern scene. “The way I sing, I’m a heart singer,” Parton says. “So unless we have technical trouble, like I’ve got an earring rattling in the microphone or something -- which I often do -- then we try to use as much of the live vocals as we can. Especially on that album, because we were all so excited. It was like we were having a big thrill, like reaching orgasm really. When something really buzzes and gels, and you’ve got all these great musicians getting off at the same time, it’s powerful.”

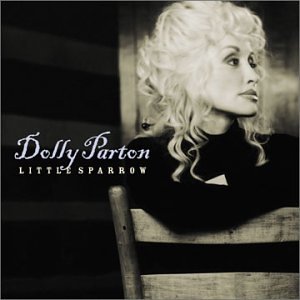

The new album, “Little Sparrow,” is both a continuation of and a departure from “The Grass Is Blue.” Most of the same musicians and singers are back, and the song choice is even more eclectic, including bluegrass arrangements of Cole Porter’s “I Get a Kick Out of You” and Collective Soul’s “Shine.” On several numbers, though, the band is augmented by the Irish traditional group Altan, and the overall feel is not so much bluegrass as what Parton has dubbed “Blue Mountain” music.

The title song is Parton’s reworking of an old mountain lament, “Come All Ye Fair and Tender Ladies,” and the album as a whole is more melancholy, with an undercurrent of pain and betrayal. “Mountain Angel” and “Down from Dover” are desperate ballads of young women loved and left, both ending up with stillborn babies. In between is a perky, romantic ditty, “Marry Me,” but in this company it leaves the listener wanting to scream a warning to its heroine.

These songs seem to come from another world than the upbeat, glamorous woman sitting in the Pierre, but Parton has always thrived on her contradictions. She grew up one of 12 children of a Tennessee sharecropper, and she has always carried her roots with her. “It’s just that old mountain way,” she says. “Basically, I have a happy heart, but I haven’t been dead nor blind neither. I grew up with all these stories, from all these sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles. I’ve seen more sorrow than one person ought to see in a lifetime, whether it’s been my sorrow or someone else’s. So I can write funny stuff like ‘He’s Gonna Marry Me,’ and then turn right around and kill the baby.”

Today, Parton seems to have found a kind of artistic peace. She still intends to record contemporary country, and would like to do a dance record with Bette Midler, along with other pop projects. Still, her next plan is for an album of traditional mountain songs, played in the old-time style, and she is positive that she has found her true musical home.

“I came out of the Smoky Mountains wanting to make a living doing this music, but I couldn’t. In order to stay in the business of show business, I had to think of all the different ways I could make it all work for me. I had to go a lot of avenues, and I don’t regret a one of ’em. I wouldn’t change a thing. But in all honesty, this is my favorite music. It’s true to my roots, it’s true to my heart, and it’s true to my voice. I think I sing this better than I sing other things, ’cause I feel it more. So I’ll do other things as well, but I’m gonna continue doing this style from now on.”

By Elijah Wald © 2020

Back

to the Archive Contents page |